Space, Myth, and Time; Artist Firelei Báez Defies the Centuries-Long Neglect of a Story Waiting to be Told.

“This is a space that would not have allowed me to exist to begin with. And I exist despite it.”

Content Warning: Use of Profanity

(Báez, in her studio. Photo: Cultured Mag)

Rolls of hair, vivid flora, and piercing eyes always seem to follow you–even through a screen. It is unsettling, nostalgic, and strikingly radical. It is here that history is torn apart and sewn together through the vastness of the large-scale paintings and installations that ornament every corner of the viewer’s peripheral. This is the very nature of Firelei Báez’s art, one that makes new out of old using color, abstraction, and appropriated materials in order to avenge the neglected narratives of culture, women, and immigrants from her world and ours.

Báez was born in the Dominican Republic, an island of Hispaniola. Coincidentally, it was there where Columbus first arrived in 1492. This was a catalytic moment for the future of the US, is the nation would come to rely on slave labor from the Indigenous and African peoples transported there from across the Atlantic on the Middle Passage. Báez told Cultured Mag, “it was the oldest colony in the world.[...] [The Dominican Republic] was like the Petri dish for modernity.”

At eight-years-old, Báez moved to Miami, Florida with her mother and sisters, since then basing herself in New York. Although her studio is located in the Bronx, the atmosphere inside is full of traces of her upbringing as a Dominican. Her art features fantastical female characters and botanical landscapes, but each piece can be drawn back to one theme: revolution.

Roping history into her work, Báez commonly paints these flourishing characters over historical construction, trade, and economic plans of the Caribbean, which she uses to “[bring] contemporary marginalia in protest to that history.” Eight of these paintings were on view with the James Cohan gallery in Tribeca in spring of 2020, Báez’s second show with the gallery. In the exhibition, she emphasizes her use of the traditional folklore she was told during her childhood.

(Photo [above and below]: Untitled (Anacaona), 2020 and detail view)

One painting depicts a snake-like creature across a 19th-century map of economic investments in the Caribbean. The figure was inspired by the Native-American Taino queen Anacaona, who chose death over becoming the mistress of one of Columbus’s captains. With her Haitian-descended father and Dominican mother, Báez lived along the border of two countries as a child, especially difficult with the historically-rooted tensions on both sides. Even with their disputes, Anacaona is a much-loved figure in Caribbean mythology that Dominicans and Haitians can easily agree on. “I was thinking of her as this avatar of female resistance, from the very first step of colonization to the present.”

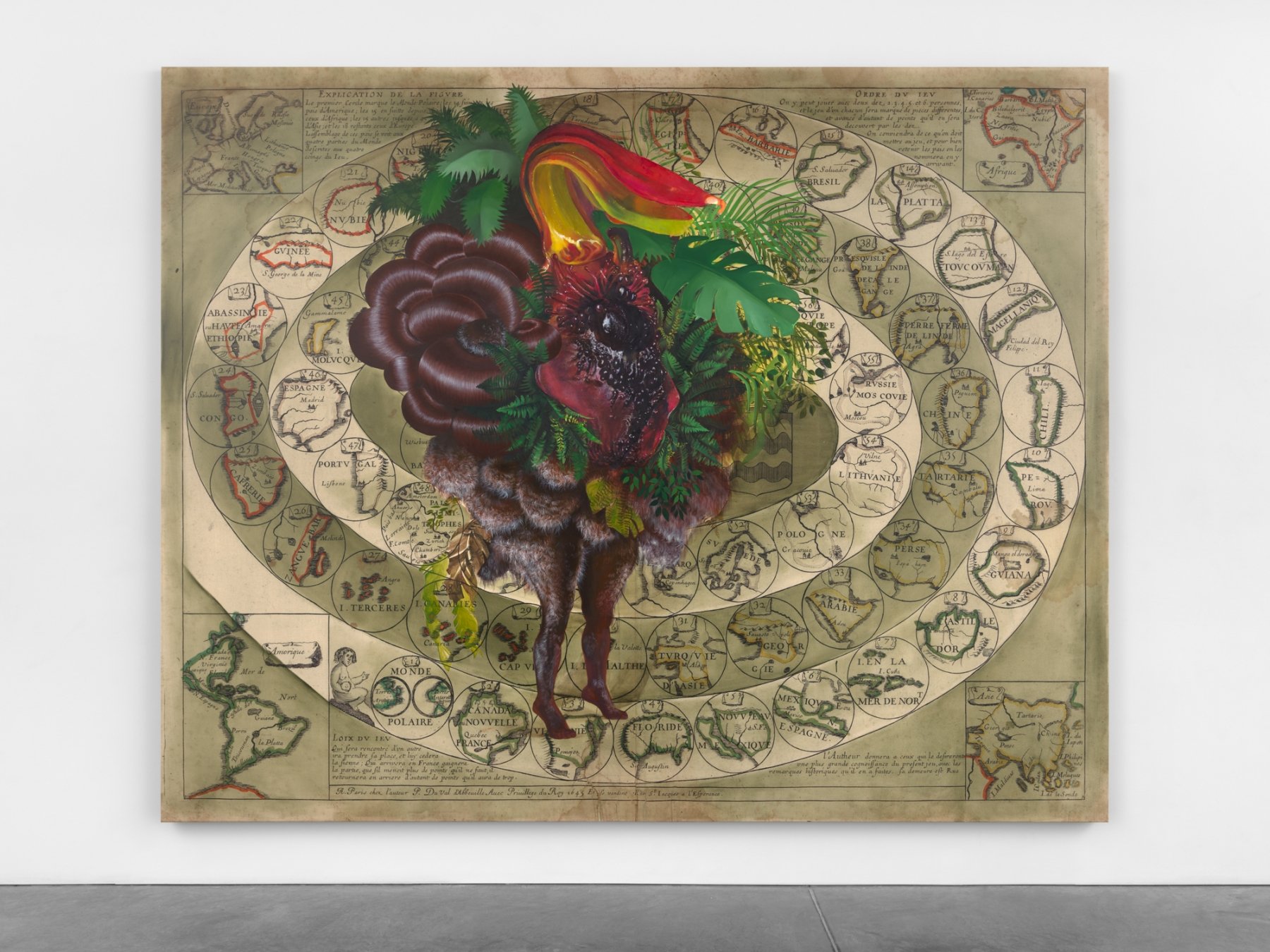

One of the most iconic motifs that appear in Báez’s work is the Ciguapa. On an old 1645 map of countries of the world forming a spiral, with France at the center, the Ciguapa reclaims attention to herself with blooming leaves and flower-like coils of hair.

(Photos [above]: Firelei Báez - Untitled (Le Jeu du Monde), 2020 and detail view)

Ciguapas are described by Báez as the “Lilith-like wild women from the forest” in Dominican folklore that have backwards-facing feet, waterfalls of hair, and live in high mountains. In a video by the James Cohan Gallery made during her 2020 exhibition, she says, “it’s kind of like the boogeyman, and then you have the feminine aspect of it to make it more untamed or something to be even more afraid of [...] she was this thing out of nature that was untamed or uncivilized.” The Ciguapa was always seen as monstrous, a warning of what she, as a woman, could not be; “everything that’s inscribed onto that figure becomes the antithesis of ideal femininity [...] I’d think, ‘There’s so much freedom in that, why would I not want to be that? Why would I not want to be untraceable and fearless?’”

Rebellion takes front stage and center in these pieces, acting as a symbol of historical reform to accommodate the perspectives of marginalized peoples during the growth of the Western world. Báez carries on with the mission to rewrite the past through the lens of one like the Ciguapa, a symbol of defiance. She described this mentality as “taking epic history with a grain of salt.”

(Firelei Báez - A Drexcyen chronocommons (To win the war you fought it sideways), 2019 - installation view at James Cohan, New York. Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle)

Báez strives to achieve what she calls a “moment of release” in her work, referring to the satisfaction in overturning the false narratives that history has long portrayed for those kept silent.

“You need to have a moment of release in it, for all of this wild action to be balanced. And so, trying to find something between both where you have this intent to be like ‘Fuck you. This is a space that would not have allowed me to exist to begin with. And I exist despite it.”

(Firelei Báez - Elegant gathering in a secluded garden (or the many bridges we crossed), 2018 - detail view. Photo: courtesy of artist and Kavi Gupta gallery)

That very point of release was designed to give the viewer peace and reconciliation. Báez achieves this through inspiration from the marginalia in Mughal paintings, “like where the painter just went wild.” Utilizing various colors and mark-making techniques, the feeling of that space is precisely yet overwhelmingly articulated. Her passion for female representation plays a role in that power. “I feel like women are some of the most generous beings in the world. Anything from who we let in to how we help the world.”

However, with the vision always comes critique; for example, Báez spoke of a white, male critic in Berlin, who criticized her overpainting of history in a “very crass, unsophisticated way.” She continued, “He needed that removal, of like, ‘oh you’re dealing with your culture out there with this thing that’s ‘other’ and that was not affected by me.”

Regardless, Báez has always been making the art for herself and women like her seeking the comfort of empowerment. In 2018, she created an installation titled “Joy Out of Fire,” which was on view at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City. The title was inspired by the letters and notes of poet Maya Angelou, who sent bouquets to at least six women in May 1994, in which each bundle arrived with a message signed “Joy, Maya Angelou.”

(Installation view of “Firelei Báez: Joy Out of Fire” at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Photo: courtesy the Studio Museum in Harlem)

Through “Joy Out of Fire'' and after months of research, Báez brings together the relationships between historical African-American and Afro-Caribbean women with histories preserved in the Schomburg archives, including 1960s pilot and advocate for underserved children, Ida Van Smith, and mixed-race child prodigy Philippa Schuyler. The murals serve an additional double purpose: an acknowledgement of Baez’s Afro-Caribbean identity and the unity in the African Diaspora’s people today.

(Photo: Jesse Costa/WBUR)

Báez’s lucidity continued to late May last year for her largest installation to date at the Institute of Contemporary Art’s Watershed in East Boston. Meant to imitate the velvet-like space of sea depths, high-painted walls tell the story of a Haitian palace in architectural ruins. It’s a replica of the Palace of Sans-Souci, built in the first northern kingdom of Haiti. Here, once-enslaved peoples built the palace shortly after a successful revolution and overthrowing of the French colonial government at the start of the 19th century, purging with it a past of mistreatment and corruption. The Sans-Souci palace was a symbol for freedom and independence, won at last. “This palace was built for a queen and was a place of joy and learning [...] Even though an incredible earthquake destroyed it, it still resonates.”

(Báez with a brush and paint can in hand as she walks through her Sans-Souci Palace installation. Photo: Jesse Costa/WBUR)

The political upheaval of Haitian history finds itself in Boston’s present, where immigrants from Haiti and other countries all around the world arrived in search of freedom. ICA chief curator Eva Respini felt that Báez’s work could make people think about the histories of migration and cultural exchange along the Boston Harbor.

Hand-cut holes on draping fabric allows light to flow in and dance on the walls, adding to a dynamic and spirited atmosphere. Triggered by motion sensors, a stream of voices play as you walk through the installation. You hear strangers talking in all different languages about their experiences as immigrants and quests to find home and family. Reminders of the past manifest into the now as wonders and questions are left unanswered, only remaining marvels at how so many peoples’ stories can come together to create a simultaneous timeline.

“And so when you traverse space, you have that whisper in your ear that reminds you of all the different choices that we made to be in the present.”

Pride, anguish, and individualism develop from the past to the present. Báez told news station WBUR about her goal with the installation, “If this can help you really see how you are a part of a larger picture, this would be the best thing that could come out of this for me. Not necessarily a beginning or end, but really seeing how you’re in a continuum with many other spaces and histories.”

The indigo color that surrounds the viewer is a crucial color in Báez’s palette; in the 18th century, enslaved generation after generation had to produce cotton that fueled the world’s economy, dying it that beautifully signature shade of indigo using techniques from West Africa. “...the figuring out how this one particular plant that was mastered in a different geography in West Africa, was there, a symbol of maybe status[...] at certain points you could exchange bodies for a bolt of this cotton dyed in indigo blue.” From the suffering of past enslavement to her childhood Caribbean pride to the blue jeans and stripes of America, indigo has an unspeakable power in every aspect of Báez’s life. It is the sea, water and sky that surrounds us all. “Just [think] of all the people who come now and who’ve been coming throughout the centuries, who had to make that choice or for whom it wasn’t even a choice. They couldn’t stay home.”

(Details on one of Báez’s Sans-Souci Palace columns. Photo: Jesse Costa/WBUR)

Every story that Báez laces into each piece tells a unique one; whether it be of power, pride, resilience, or a dive of hope straight into the unknown. Her work is a belief of hope and a recognition of the losses of the unheard and overshadowed, to those having to live between the spaces every day.

“...because of the different diasporas that have gone through our countries–it’s something that you have to survive. You and I are here because somebody decided to survive…one [feeling] does not erase the other, we are a whole other way of being.”