The Impacts of War on Ukrainian Scientists

Fedir Shandor Giving A Lecture (Image Source: NBC)

What you’re looking at is a picture of Fedir Shandor, a tourism professor (yes, tourism) at Uzhhorod National University in Ukraine, giving a lecture to his students. Looks pretty different from most lectures, doesn’t it? That’s because Shandor enlisted in the Ukrainian army on the first day of Russia’s invasion. Now, he continues giving lectures from the trenches, literally in between combat shifts. If Russian soldiers attack the area around him, Shandor hides in a dugout and continues the lecture, noting that the noise isn’t loud enough to disturb his lesson. "We are fighting for an educated nation. If I don’t give lectures, it will be a pity," he said in a statement from the university.

Shandor is one of the many scientists, researchers, and intellectuals who lived and worked in Ukraine before the beginning of the war. In 2020, their achievements made Ukraine the 14th best country in terms of Science and Technology, per the Good Country Index. That’s not bad for a country that, before the war, ranked 35th in population.

But Russia’s invasion has changed the priorities of many Ukrainian scientists. Take Maryna Viazovska, the second woman to ever win a Fields Medal, which is the highest prize in mathematics. Although she grew up and was educated in Kyiv, she had been living abroad for over a decade when the war began. “For me, mathematics and strong emotions are incompatible,” Viazovska explained. “When the war started, at first I couldn't do anything at all. ”

Viazovska in 2013 (Source: Wikipedia)

Viazovska wasn’t the only one who felt that way. In a study conducted from April to May of 2022, 72.9% of the Ukrainian scientists and researchers participating said it was impossible to “be engaged in research activities to the same extent as in pre-war times.” Some of the main reasons include not feeling safe, not being able to show up to their workplace even though they need to, and problems with internet access, electricity, and communication. Some people even reported being disinterested in work that previously fascinated them, which is totally understandable given the violence occurring in Ukraine. If everything that matters to you is in real danger, how can you go back to something theoretical?

In Kharkiv, an academic city kind of like Ukraine’s Cambridge, one college and one university have been completely destroyed, while 29 colleges and 23 universities have been damaged. This includes V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University. In addition to being a great Ukrainian school, Karazin is home to many researchers and scientists and is even one of the oldest universities in Eastern Europe.

Karazin University Before Russia’s Invasion (Source: Wikipedia)

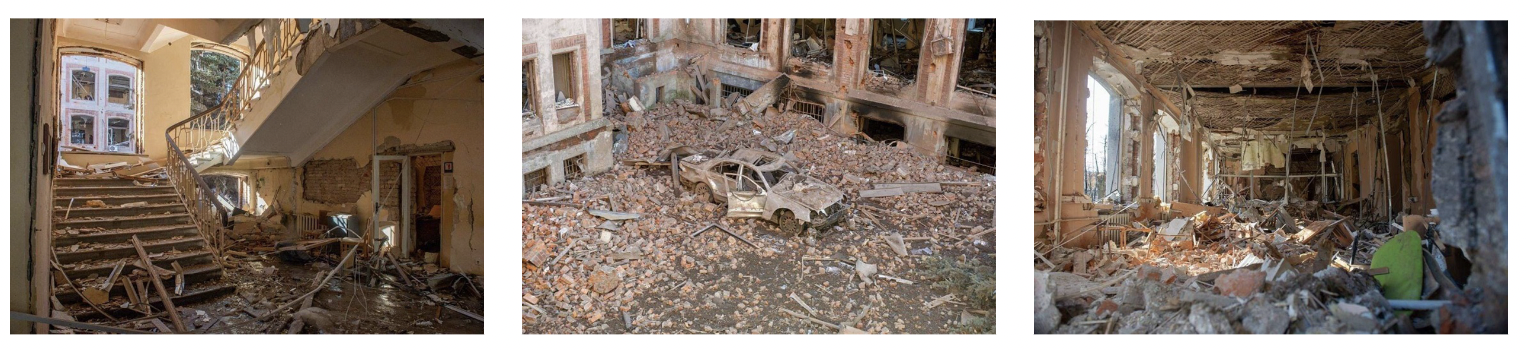

In early March of last year, Russian missiles hit Karazin’s campus, damaging multiple buildings and destroying its Institute of Public Administration. Moreover, missiles exploded the university’s rare book library, which included ancient handwritten manuscripts, personal papers of scientists, and Ukrainian books from the 16th and 17th century. The books became damaged by shards of glass from exploding windows, soaked in dirty water from ruptured pipes, and vulnerable to the elements because of the fallen ceiling. The University’s librarians had to figure out how to save what was left of these 60,000 rare books before they were ruined by mold and fungus.

Karazin University now (Source: Chytomo)

About 15% of Karazin students have dropped out or transferred to other schools. For those who remain, classes have since gone virtual. The decrease in work means that professors have been laid off, or lost their jobs completely. Some students have joined the military or are volunteering for the war effort, including six teachers and five students who have died due to the violence. Others continue their studies abroad, or even stay behind to protect their research, like entomologist Yuliia Guglya. After February 24th, 2022, Guglya moved into the basement of Karazin’s Museum of Nature, and became the resident curator of the 215-year-old collection.

Guglya and some of the prize specimens in the Museum of Nature’s basement. (Source: R. STONE/SCIENCE)

Guglya and some of the prize specimens in the Museum of Nature’s basement. (Source: R. STONE/SCIENCE)

While Russia limits Ukrainian innovation through acts of aggression, Ukrainian youth are continuing to showcase the nation’s scientific capabilities. Just within the past year, Ukrainian high school students have gotten first place in the International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO), and been finalists in the International Science and Engineering Fair. The technologies these teens have developed include safer insecticides and less-toxic cures for cancer. In times of peace, these exceptional kids could have gone on to Ukrainian universities and studied with some of the world’s brightest minds. But now, they’ve either left their families to seek safety and higher education overseas, or are continuing their work in bomb shelters with the risk of losing their lives at any moment.

As you sit here reading this, some of Ukraine’s brightest minds are dying fighting the Russian Army. These include 28 year old Vladislava Chernykh, a graduate student of the National Pharmaceutical University at Karazin. She had wanted to study virology and complete her postdoctoral, but in May she enlisted in the Ukrainian army as a combat medic because she felt that it was her duty to help her country. On December 28th, Chernykh was killed by Russian shrapnel near Bakhmut.

Vladislava Chernykh (Source: Sunday Post)

People who fought with Chernykh described her as brave, quiet, and serious. If Russia hadn’t invaded, who knows what vaccines she could have helped develop, or how many more lives she could have saved. We certainly don’t, because she died for her country.

From the framework beehive to helicopters to innovations in physics, immunology, bacteriology, and medicine, Ukrainian scientists have improved the lives of millions with their innovations and discoveries. Now, the lives, careers, and future contributions of these naturally peaceful people are at stake. As they continue their pursuit of knowledge, it is up to us to make their discoveries possible.

Want to help Ukrainian scientists and researchers? Check out the Safe Passage Fund, which was created by the United States National Academy of Scientists to help Ukrainian scholars and their families relocate to safe places for the remainder of the war. Additionally, consider donating to MIT’s program, Yulia’s Dream. Named after Yulia Zdanovska, a brilliant young mathematician who was killed by a Russian missile, this project allows Ukrainian high schoolers to conduct mathematical research under mentors from MIT.