Animals: Victims of Violence

A three-year old cat named Zenia is rescued by paramedics after her family was forced to flee without her. Zenia lives near Bucha, where the atrocities of Russian soldiers are so severe that they should count as genocide. (Source: The Guardian)

Let’s say that you’re living in Ukraine with your pet cat when the war begins. Assuming you’re lucky enough to be able to flee, what do you do with your pets?

This is a decision that many of the human parents of over 750,000 dogs and over 5.5 million cats have had to make. Taking a pet with you is not easy, especially when Russian soldiers could shoot at your car and get you--and your pet--killed. So, a lot of people choose to stay behind. In Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital and one of the best-guarded regions of Ukraine, 84% of the people who stayed as of October 2022 cited their pets as their main reason for staying. Similarly, almost all of the people surveyed who left Kyiv said that knowing that their pets were allowed on trains, buses, and across the border helped their decision.

But let me be clear: taking your pets with you isn’t always an option. Not a lot of studies have been done on the effects of psychological trauma of war for cats. The loud noises, explosions, and smoke can send them into shock, make them run away, or turn feral. But they may also be better off living outside, where they can hunt for food without being trapped in residential buildings, which are frequently targeted by Russia. If it’s a matter of life and death, isn’t it better if part of our family survives as opposed to no one?

Barsuk, my Uncle’s cat. His name means beaver in Russian. Russian was a dominant language in Kharkiv before the invasion. (Source: Sergiy Sitkovskyy)

Some pets even protect their humans from Russian aggression. Take, for example, my aunt and uncle’s cat, Barsuk (pronounced Bar-sook), who used to live with them in Kharkiv. When the war began, little Barsuk would sense the missiles attacking Kharkiv even before the air raid sirens went off, giving my aunt more time to seek shelter. Because Kharkiv is so close to Russia, it takes minutes for missiles to hit their target. One day, a missile hit near my aunt and broke her windows. If Barsuk hadn’t started meowing, who knows if she would have survived. This little kitty saved her life.

And while traveling within Ukraine with your pet is hard, it gets even harder at the border. Irina Ponomarenko, the director of a Dnipro animal shelter, told NPR that her shelter mostly houses pets whose owners are forced to abandon them. "Often people fleeing the war are given just minutes to evacuate and they take the most valuable thing — their animals," she says. "When they arrive their houses have often been destroyed, their cars have been shot at. They are confused and crying, their animals are often injured or sick because there are no animal clinics in the east any longer."

Some people bring their pets and struggle on. One organization that helps evacuate animals from Ukraine was PETA, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. One member, Daniel Cox, told inews that he had to negotiate with Polish authorities to help people bring as many as twelve cats over the border. “That number was really not unusual,” he says.

Ukraine has a large number of stray cats in addition to those left behind when their owners flee. In Borodianka, an 11 year old girl named Veronika Krasevych looks after stray cats. She finds their hiding spots under wreckage and in playgrounds, and makes sure they are well fed. Like them, she’s lost her home and belongings to Russian aggression. I can’t imagine how her family can afford to feed all these cats (war like this does not do good things for a country’s economy), but studies have shown that interacting with animals, even in grievous circumstances, can reduce stress and give people a sense of purpose and hope.

At Feldman Ecopark Zoo in Kharkiv, Ukraine, animal rehabilitation programs have been underway since Russian President Vladaimir Putin’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 to help Ukrainian children recover from the trauma of war. Their Centre of Psychological Rehabilitation utilized programs designed by medical professionals from leading Ukrainian organizations like the National League of Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics and Medical Psychology of Ukraine. But now, even that has come to a stop because of how unsafe Kharkiv is. Last April, five zookeepers and over 100 animals from Feldman Ecopark died. Some died of heart failure, some from shelling, and two zookeepers were shot to death by Russian paratroopers. Since then, organizations have been working to evacuate the animals that are still alive.

CAPTION: Damaged animal enclosures at Feldman Ecopark Zoo in Kharkiv (believe me, there are many more gruesome images). Source: NPR.

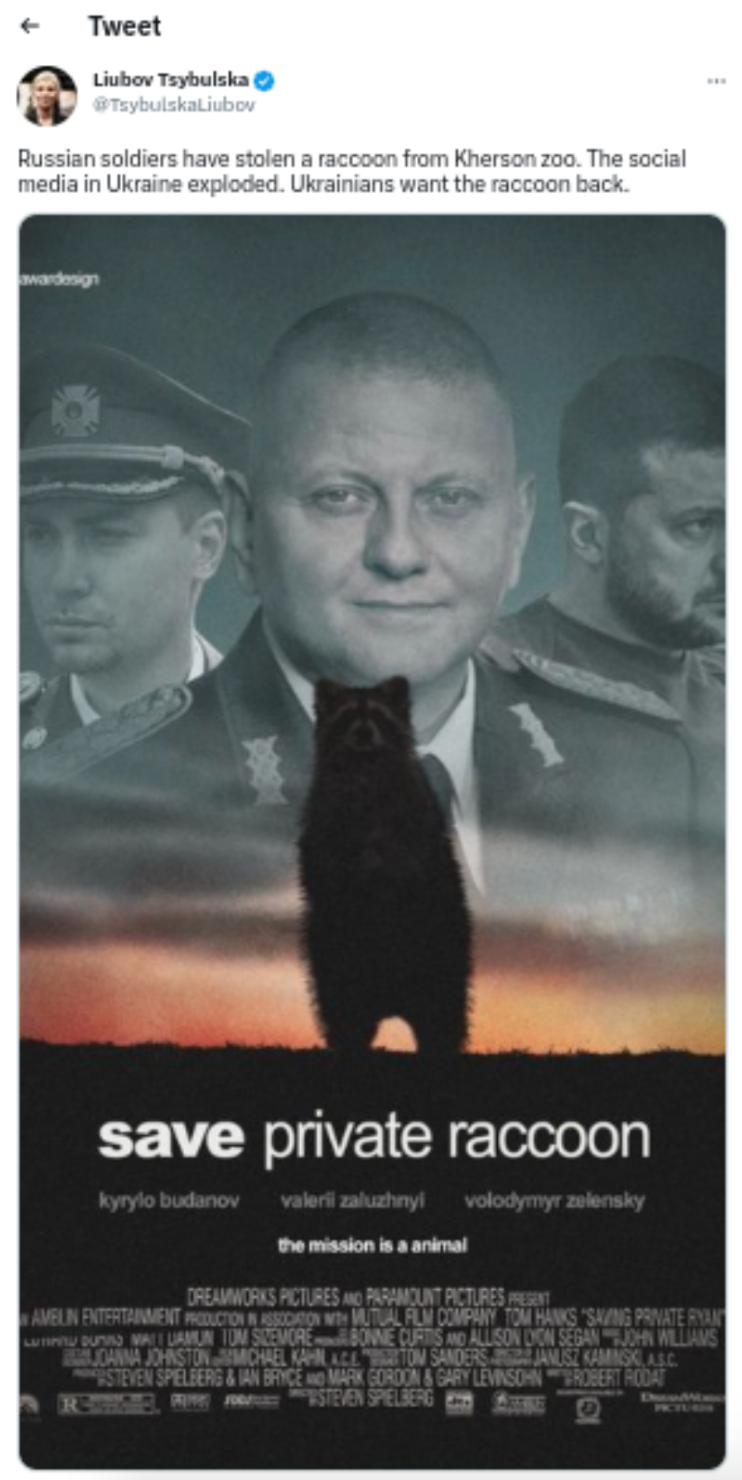

Other zoos were not so lucky. In Kherson, retreating troops kidnapped several animals, including a baby raccoon that has now become a subject of Russian and Ukrainian propaganda.

Source: Liubov Tsybulska (Twitter)

Even zoos that weren’t attacked face food and water shortages. Not to mention, no one really knows how animals will respond to explosions. In Kyiv Zoological Park, one of the largest zoos in the world, some animals were given sedatives or moved underground to protect them from the shock of loud noises. Zookeepers who were unsafe in their homes moved into the park, helping to care for the animals.

It isn’t these animals’ faults that their homes are being destroyed or their owners are being forced to flee. It’s not Ukraine’s fault that Ukrainians are dying every day as war continues around them. But because of Russian aggression, Ukraine’s people, and animals, are continuing to live at risk.

Want to help Ukrainian animals? Consider donating to the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria’s Ukraine Emergency Fund, a zoo like Feldman Ecopark, or to the Aid for the Animals of Ukraine Fund from Humane Society International.